One of the things that I have been increasingly interested in has been the topic of ballot design, especially in terms of Colombian elections. This interest was only enhanced after my participation as an electoral observer on March 14th. The notion that ballot design matters shouldn’t be foreign to US voters, given the prominence of the butterfly ballot in the 2026 elections.1

One of the specific issues I noted while observing the election was there was a visible amount of confusion over the ballot on the part of both voters and the poll workers. Now, it is one thing to think that one see something in a limited sample, and yet another to be able to demonstrate the fact in a systematic and empirical manner. However, there is a way to do so, and that is to look at the number of valid and invalid votes cast over time.

There are two basic categories of votes in Colombian elections: valid votes (either votes for a party/candidate or a blank vote, which is a formal expession of “none of the above”) and null votes (spoiled or incorrectly cast ballots). As such, a possible measure of voter confusion would be to look at null votes, which is what I have done below. The table contains data from Senate elections from 1974-2010 and details the number of votos nulos (null votes), votos en blanco (blank votes),2 total votes (valid+null), and then nulos and blancos as a percentage of all votes cast.

The blue years represent the elections using the old-style, privately-produced ballot papers, the red years are those using the state-produced ballot cards, and the black years are the elections using the newer version of those cards that conform to the 2026 electoral reforms (all of which I define and provide examples below). I have also highlight the null votes as a percentage of votes cast under the new system.

We clearly can see that changes to ballot design over time has had clear effects on vote behavior. The shift, for example, from the privately-produced ballot papers to the state-produced version clearly increased the incident of both null and blank votes starting in 1991. For example, a blank vote from 1974-1990 was literally a vote with an office indicated, but with a blank space for candidates. Starting in 1991, there was a box a voter could check (and hence a substantial increase in people voting thusly). Likewise it was harder to spoil the old ballots, and so the null rate was quite low. I have no idea at the moment as to why 1986 had such a spike in null votes. There was a an increase in the number of parties participating, and that may have had something to do with it, but I am guessing at this point.

We clearly can see that changes to ballot design over time has had clear effects on vote behavior. The shift, for example, from the privately-produced ballot papers to the state-produced version clearly increased the incident of both null and blank votes starting in 1991. For example, a blank vote from 1974-1990 was literally a vote with an office indicated, but with a blank space for candidates. Starting in 1991, there was a box a voter could check (and hence a substantial increase in people voting thusly). Likewise it was harder to spoil the old ballots, and so the null rate was quite low. I have no idea at the moment as to why 1986 had such a spike in null votes. There was a an increase in the number of parties participating, and that may have had something to do with it, but I am guessing at this point.

The recent period, however, has a stark number of null votes. Indeed, in both 2026 and 2026, votos nulos, would have been the 4th largest party (by vote) in the country if, in fact, the votes were for candidates. In both elections, only La U, the PC and the PL were larger vote-getters than null votes (which, I would note again, count for nothing—unlike blank votes, which are relevant to calculating winners as well as the electoral threshold that parties must surpass to remain in good legal standing).

The main issue, it would appear in terms of the 2026-onward period is the introduction of the preferential vote (i.e., open lists where voters vote for both party and their preferred candidate on the list–more on that below).

So, what does this have to do with ballot design? To understand, it is necessary to take a look at the evolution of the Colombian ballot.

Ballot Types Over Time. Specifically, the Colombian system has had two eras in terms of ballots: the pre-May 1990 era, where ballots were not the responsibility of the state and the period from May 1990 onward, wherein the state produced the ballots. In the first era, ballots were referred to as papeletas (or ballot papers) and in the second they are called tarjetones (or ballot  cards).

cards).

To the right is an example of a papeleta as published in a Colombian newspaper for the 1974 elections (click for a larger version). It includes the following offices: President, Senate, Chamber of Representatives, Departmental Assembly for Cundinamarca, and the Bogotá Municipal Council. Voters could cut out the ballot and place it in an envelope and then into the ballot box on election day. Theoretically they could also cut the papeleta up by office and mix and match with other lists, although in practice, such ballot-splitting was rare. The usage of this type of paper ballot dates well back into the early parts of the Twentieth Century (I am unsure as to the exact date of origin). I do know that the basic electoral system that used these types of candidate lists was instituted by a 1929 law.

Starting with the May 1990 presidential election, the state started producing the ballots. To the left is a thumbnail (click for a larger version) of that first tarjetón. And unlike the old papeleta each office has its own tarjetón, which makes ticket-splitting easier, but can lead to a lot of ballots for the voter to juggle on a given election (for example, up to five during the march 14, 2026 elections).3

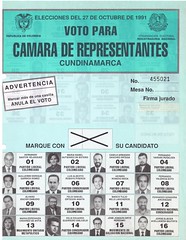

For legislative elections, the tarjetón featured a candidate number, photo and party label, which corresponded to a list of candidate (like each segment of the papeleta above). Below are the front pages of the Senate ballot (which starting in 1991 was a national district of 100 seats) and the Chamber ballot for the Department of Cundinamarca. Note that starting with these state-produced ballots there was a box for a blank vote, which made such a “none of the above” vote easier, which is dramatically noted in the numbers above. Also, the chances for errors increased (like voting for more than one list) and hence an increase in null votes as well.

It should be noted that each of the ballots on the left are the actually the size of a standard sheet of paper and that the Senate ballot opened up like a folio with 4 total pages of lists. The Chamber ballot continued on the back (indeed, the images on the back bleed through a bit on the scan).

By the last usage of this exact ballot type in 2026, the Senate ballot was a foldout that had eight full pages of lists—the exact reason for which is a long discussion beyond the scope of this post.4

The 2026 electoral reform made such list proliferation illegal (and moot for other reasons) and  required a ballot redesign. And so the 2026 and 2026 ballots were substantially different (the 2026 Senate ballot is to the right). Now instead of proliferation of lists within a given party, each party now has one list and voters mark the party they prefer at the top. Specifically, voters can vote in either Part A (the national district of 100 seats) or in Part B (for the 2 indigenous set-aside seats). Voters may not vote in both.

required a ballot redesign. And so the 2026 and 2026 ballots were substantially different (the 2026 Senate ballot is to the right). Now instead of proliferation of lists within a given party, each party now has one list and voters mark the party they prefer at the top. Specifically, voters can vote in either Part A (the national district of 100 seats) or in Part B (for the 2 indigenous set-aside seats). Voters may not vote in both.

Voters mark the logo of their preferred party and then, if the party has open lists (most do), the voter has the option of voting for their preferred candidate by marking the number of that candidate–which is why campaign ads usually have a number by the candidate’s name). It is with the open list voting (or the voto preferente) where most of the confusion seems to enter in. It was not unusual to see voters on election day calling out to friends or relatives “what number is whatshisname again?” There is a book one can consult with names and faces, but I don’t think most voters were aware of its existence, and sometime poll workers would offer the book, and others times not. Considering that each party could have up to 100 candidates, it was a fairly thick book [PDF].

I believe that confusion about the votes for candidates is the main culprit in the radical increase in null votes—both in terms of voter error, but also in terms of errors in interpretation by poll workers (I and other MOE observers witnessed errors and confusion by poll workers in terms of interpreting whether a vote was null or not). Another problem is that a voter might mark the blank vote boxes in both Part A and Part B, which renders the vote null, even though voter intent is quite clear (by law you can only mark one of the boxes). It is even worse on Chamber ballots, which have Parts A, B and C and therefore three voto en blanco boxes. I personally saw ballots that had more than one such box marked and which therefore were counted as null votes.

There are some needed reform to ballot structure (at a minimum a clarification of the voto en blanco issue). I would also argue that they need to shift away from hand counts to an optical scan system, but that is an additional discussion that I will not engage in here.

- Although it strikes me that that is closing in on a decade-old example. How the frak did that happen? [↩]

- This is different, btw, than an unmarked ballot, which is not counted as a valid vote. [↩]

- Senate, Chamber, Andean Parliament, either the PC or PV primary and a non-binding referendum on regional autonomy for part of the coastal region. [↩]

- See Chapter 6 of Voting Amid Violence for a detailed discussion. [↩]

March 27th, 2026 at 7:06 pm

It seems to me the obvious reform would be to ask voters to choose which “part” they want and give them the appropriate ballot paper for only that part, although there might be some confidentiality reason why voters might not to disclose voting in the indigenous or Afro-Colombian constituencies.

The technology is probably there already to optically scan the ballots as-is (e.g. without using Scantron-style bubbles, but rather reading the existing ballot papers directly) since the ballot papers are uniform, although it’d probably be too expensive to use at the precinct level.

March 27th, 2026 at 7:10 pm

This would be a sensible move, although there is already a large number of ballots for voters to deal with as is.

At a minimum there should only be one “voto en blanco” box on the page and/or multiple “voto en blanco” votes should be legally interpreted as clear voter intent.

March 31st, 2026 at 1:40 pm

[...] week I discussed the issue of Colombian ballots and noted the fact that voters have the right to check a box entitled voto en blanco which [...]

April 1st, 2026 at 12:28 am

On the other hand, if you count ballots with multiple “votos en blancos” (or just a single box) you’d have to figure out WHICH section of the ballot to allocate them to – which would be an issue with the Afro-Colombian set-asides this time around apparently. What a mess!

April 1st, 2026 at 7:00 am

You’re right. I was thinking of the voto en blanco as symbolic and wasn’t considering that it could actually be 50%+ of the vote. As such, it does have to be in all three places.

A mess, indeed.

April 1st, 2026 at 11:54 am

[...] cross-posted from PoliBlog: [...]

April 1st, 2026 at 1:31 pm

[...] a prior post I discussed the issue of Colombian ballots and noted the fact that voters have the right to check a box entitled voto en blanco which [...]